| Learn Chinese | Traditional Chinese Culture | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Chinese culture is over 5000 years old, which is one steeped in tradition, history and values. Chinese people are notoriously warm and welcoming, and wherever you are in China, you will encounter a wonderful culture through Chinese language. The Chinese language is fundamentally built on Chinese culture. The fascinating culture is a major reason for most foreign learners to learn Chinese.

If you want to really grasp the culture, it is advisable to study Chinese language to really understand the foundation of the culture and its people. By learning the Chinese Language, you will learn another culture and another way of looking at the world. Learning a language gives you a better opportunity to understand the splendid traditions in literature, the arts, and cuisine behind the culture.

Our Chinese Culture Course aims to help you understand more about China and its people, culture and customs. ECS offers acculturation courses so that you can get to know more Chinese people’s lives and improve your life in China more easier and interesting. The culture courses focus on specific aspects of traditional Chinese culture.

Yum cha is a southern Chinese style morning tea, which involves drinking Chinese tea and eating dim sum small dishes (steamed, fried or baked sweets). In specialist restaurants, staff will commonly wheel around heated trolleys serving small yum cha dishes. Yum cha in Cantonese Chinese literally means "drink tea", while ban ming is a more poetic term meaning "tasting of tea". In the US and UK, the phrase dim sum is often used in place of yum cha; in Cantonese, dim sum (點心) refers to the wide range of small dishes, whereas yum cha, or "drinking tea", refers to the entire meal. Dim sumSimilarly to a Western morning or afternoon tea, despite the name, yum cha is focused as much on the food items served with the tea as the tea itself. These food items are collectively known as "dim sum", a varied range of small dishes which may constitute or replace breakfast, brunch or afternoon tea. Dishes are usually steamed or fried and may be savoury or sweet. They include steamed buns such as char siu baau, assorted dumplings, siu mai, and rice noodle rolls, which contain a range of ingredients, including beef, chicken, pork, prawns and vegetarian options. Typical dessertsinclude egg tarts, sai mai lo (tapioca pudding) and mango pudding. Many yum cha restaurants also offer plates of steamed green vegetables, roasted meats, congee porridge, and soups. Dim sum can be cooked by steaming and frying, among other methods. The dim sums are usually small and normally served as three or four pieces in one dish. It is customary to share dishes among all diners on the same table. Because of the small portions people can try a wide variety of food. Traditionally, the cost of the meal was calculated based on the number and size of dishes left on the patron's table at the end. In modern yum cha restaurants, dim sum servers sometimes mark orders by stamping a card on the table. Servers in some restaurants even use different stamps so that sales statistics for each server can be recorded. Customs and etiquetteIt is customary to pour tea for others before filling one's own tea cup. It is most gracious to be the first to pour tea. When tea drinkers tap the table with two (occasionally one) fingers of the same hand, an action known as 'finger kowtow', it means thanks. According to a just-so story, this gesture recreates a tale of Imperial obeisance and can be traced to Emperor Qianlong, a Qing Chinese emperor, who used to travel incognito. While visiting South China, he once went into a teahouse with his companions. In order to maintain his anonymity, he took his turn at pouring tea. His stunned companions wanted to kowtow for the great honour but to do so would have revealed the identity of the emperor. Finally, one of them tapped three fingers on the table (one finger representing their bowed head and the other two representing their prostrate arms) and the clever emperor understood what he meant. From then on, this has been the practice.

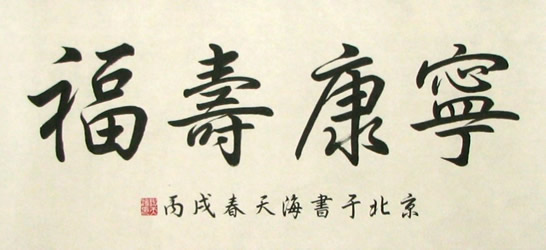

Chinese calligraphy is a form of calligraphy widely practiced in China and revered in the Chinese cultural sphere. The calligraphic tradition of East Asia originated and developed from China. There is a general standardization of the various styles of calligraphy in this tradition. Chinese calligraphy and ink and wash painting are closely related, since they are accomplished using similar tools and techniques. Chinese painting and calligraphy distinguish themselves from other cultural arts because they emphasize motion and are charged with dynamic life. According to Stanley-Baker, "Calligraphy is sheer life experienced through energy in motion that is registered as traces on silk or paper, with time and rhythm in shifting space its main ingredients." Calligraphy has also led to the development of many forms of art in China, including seal carving, ornate paperweights, and inkstones.

Evolution and stylesChinese characters can be retraced to 4000 BC signs (Lu & Aiken 2004). The contemporary Chinese characters set principles were already visible in ancient China's Jiǎgǔwén characters carved on ox scapulas and tortoise plastrons around 14th - 11th century BCE (Lu & Aiken 2004). Brush-written examples decay over time and have not survived. During the divination ceremony, after the cracks were made, characters were written with a brush on the shell or bone to be later carved.(Keightley, 1978). With the development of Jīnwén (Bronzeware script) and Dàzhuàn (Large Seal Script) "cursive" signs continued. Moreover, each archaic kingdom of current China had its own set of characters.

In Imperial China, the graphs on old steles — some dating from 200 BC, and in Xiaozhuan style — are still accessible. In about 220 BC, the emperor Qin Shi Huang, the first to conquer the entire Chinese basin, imposed several reforms, among them Li Si's character unification, which created a set of 3300 standardized Xiǎozhuàn characters.Despite the fact that the main writing implement of the time was already the brush, little paper survives from this period, and the main examples of this style are on steles. The Lìshū style (clerical script) which is more regularized, and in some ways similar to modern text, were also authorised under Qin Shi Huang. Kǎishū style (traditional regular script) — still in use today — and attributed to Wang Xizhi (王羲之, 303-361) and his followers, is even more regularized. Its spread was encouraged by Emperor Mingzong of Later Tang (926-933), who ordered the printing of the classics using new wooden blocks in Kaishu. Printing technologies here allowed shapes to stabilize. The Kaishu shape of characters 1000 years ago was mostly similar to that at the end of Imperial China.But small changes have been made, for example in the shape of 广 which is not absolutely the same in the Kangxi Dictionary of 1716 as in modern books. The Kangxi and current shapes have tiny differences, while stroke order is still the same, according to old style. Styles which did not survive include Bāfēnshū, a mix of 80% Xiaozhuan style and 20% Lishu. Some Variant Chinese characters were unorthodox or locally used for centuries. They were generally understood but always rejected in official texts. Some of these unorthodox variants, in addition to some newly created characters, were incorporated in the Simplified Chinese character set.

Cursive styles such as Xíngshū (semi-cursive or running script) and Cǎoshū (cursive or grass script) are less constrained and faster, where more movements made by the writing implement are visible. These styles' stroke orders vary more, sometimes creating radically different forms. They are descended from Clerical script, in the same time as Regular script (Han Dynasty), but Xíngshū and Cǎoshū were used for personal notes only, and were never used as standard. Caoshu style was highly appreciated during the reign of Emperor Wu of Han (140 BC−87BC).

Examples of modern printed styles are Song from the Song Dynasty's printing press, and sans-serif. These are not considered traditional styles, and are normally not written. the evolution of character "horse"

Chinese chess has a long history. Its origin has not been confirmed yet. But judging by its rules, we can conclude that the origin of Chinese chess was closely related to military strategists in ancient China. During the Spring and Autumn Period and the Warring States Period, wars were fought for years running. A new chess game was patterned after the array of troops. This was the earliest form of Chinese chess. During the Wei, Jin and Northern and Southern Dynasties, a kind of chess game was popular among the people. It laid a foundation for the finalized pattern of the Chinese chess. In ancient times, the Chinese chess was always enjoyed by both highbrows and lowbrows. During the reign of Suzong of the Tang Dynasty, Prime Minister Niu Sengru wrote a fake story about chess. That occurred during the Baoying period, so it was named Baoying chess. Baoying chess had six pieces. He wrote about the rules of the chess. Baoying chess produced a significant influence on the chess in subsequent years. Three forms of chess took shape after the Song Dynasty. One of them consisted of 32 pieces. They were played on a chessboard with 9 vertical lines and 9 horizontal lines. Popular in those days was a chessboard without a river borderline. The Chu River and Han Borderline were added later. This form has lasted to this day. With the economic and cultural development during the Qing Dynasty, the Chinese chess entered a new stage. Many different schools of chess circles and chess players came into prominence. With the popularization of the Chinese chess, many books and manuals on the techniques of playing chess were published. They played an important role in popularizing the Chinese chess and improving the techniques of playing in modern times.

Ma jang is a game that originated in China. It is commonly played by four players. Similar to the Western card game rummy, ma jang is a game of skill, strategy, and calculation and involves a degree of chance. The game is played with a set of 144 tiles based on Chinese characters and symbols, although some regional variations use a different number of tiles. In most variations, each player begins by receiving 13 tiles. In turn players draw and discard tiles until they complete a legal hand using the 14th drawn tile to form four groups (melds) and a pair (head). There are fairly standard rules about how a piece is drawn, stolen from another player and thus melded, the use of simples (numbered tiles) and honors (winds and dragons), the kinds of melds, and the order of dealing and play. However there are many regional variations in the rules; in addition, the scoring system and the minimum hand necessary to win varies significantly based on the local rules being used.

Jiaozi (饺子), a kind of dumpling, is a favourite food of Chinese people. It is usually a semicircular wheaten food with stuffing. In most areas of China, jiaozi is made when people celebrate the Spring Festival or other festivals and entertain relatives and friends. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

wechat or phone call (+86) 13923481710

support@edward-chinese.com

Bai Hua Plaza,10th floor,Room 1011-1012,Chan Cheng District, Foshan,China

.jpg)

.jpg)

.png)